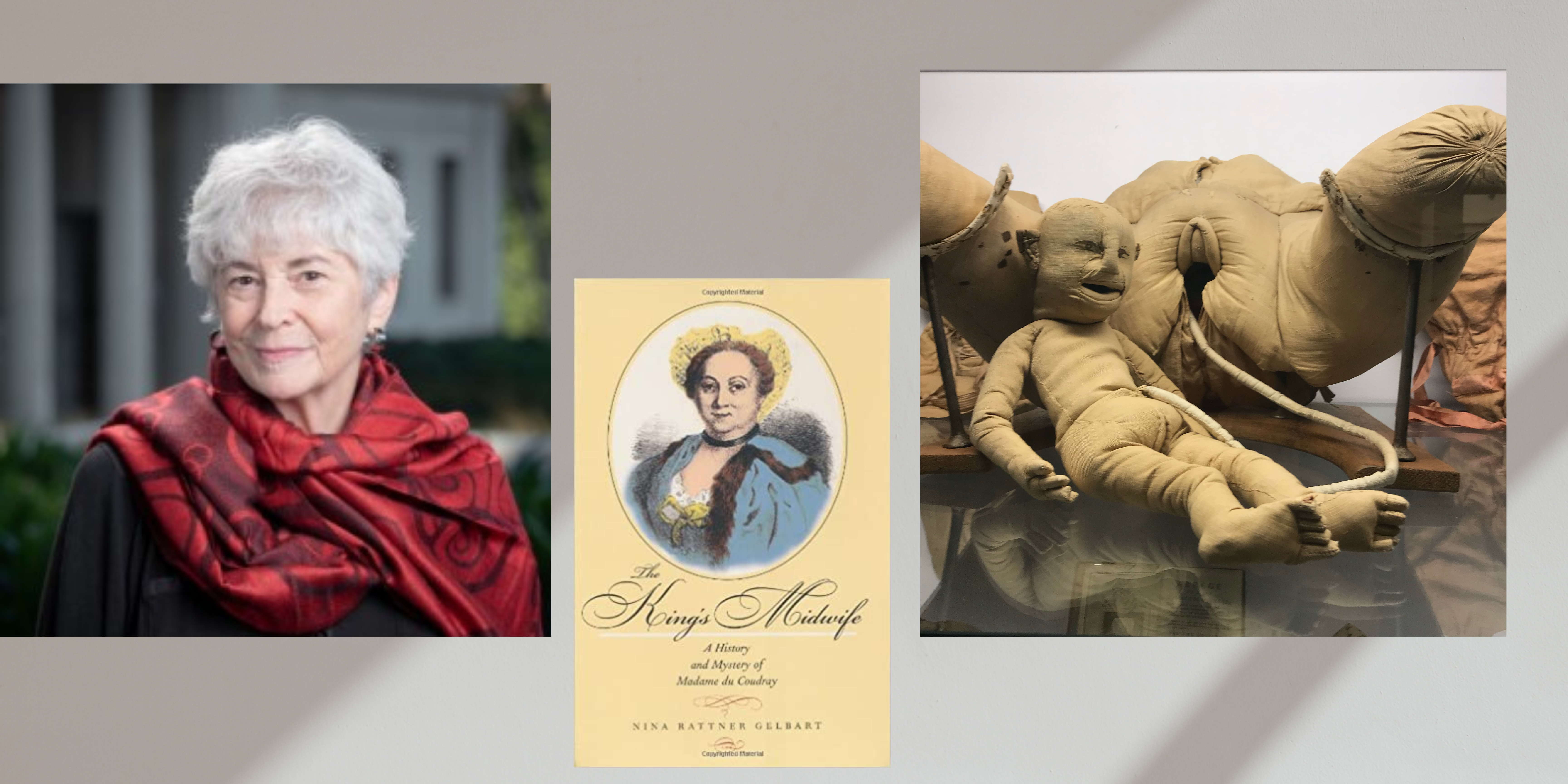

I’ve stumbled across The King’s Midwife; A History and Mystery of Madame du Coudray when I was researching my latest novel The School of Mirrors and needed some information on French midwifery in the 18th century. The book captivated me at once. Here was a story of, an extraordinary Enlightenment woman, an accredited midwife, an educator, an inventor of a teaching tool which can still be admired at the Musée Flaubert in Rouen. Knowing that Madame du Coudray had a place in my novel, I reached out to her biographer, Nina Rattner Gelbart.

ES: How did you come across Madame du Coudray?

NRG: I was doing research on little-known female journalists in the 18th century for my first book, a study of a periodical called Le Journal des Dames. In the 1700s there were quite a few collected biographies called Femmes célèbres, mostly about queens and royal mistresses, but also full of information on other important women of that time who were famous then but essentially forgotten today. Among them was this extraordinary midwife, commissioned by King Louis XV to travel around France teaching obstetrics. I turned up many mentions of her, saying that she had invented a mannequin, and written a textbook on birthing. The dates and other details in these mini-bios turned out to be all wrong, but the contours of an amazing story were there. I was fascinated, and decided that as soon as I was done with my book on the Journal des Dames I would learn more about Mme du Coudray. Much to my astonishment, I found that hardly anything had been written on her since her own time! So I sent inquiries to each of the 90-plus French departmental archives, asking if they had any documents on her. I could tell them what archival series to look in, because if she was sent by the king she would have had to be in touch with his minister of finance. Some archivist said no, some said maybe, but many said they had a rich supply. So, over the course of about 8 years—whenever I had free time from my professor job or a sabbatical semester or a summer—I traveled around France gathering and reading all traces of her I could find. Because her mission was official, that is because the king had recognized her talent and commissioned her to basically arrest infant mortality (!), hundreds of letters existed, to her, about her and by her. I was in heaven. There are hardly any women, especially in the 1700s, who left that kind of paper trail.

ES: How do you see her, you who have researched her life, immersed yourself in her work, her friendships, her achievements?

NRG: I was from the first, and still am, completely smitten. Madame du Coudray had a strong sense of self and, out of sheer guts and stamina, she invented a life-long patriotic and humanitarian mission to save babies for France. This was a job envisioned by her and then royally created for her, completely unprecedented. She persuaded the king that she had something unique to offer to the nation. She was a strong, tough person, but just imagine what she had to deal with as she moved from one French city to another, set up her operation, taught the huge number of very young women that the local parish priests had selected for her as potentially eager student midwives. Everywhere she went she had to deal with administrators appointed by the Court in Versailles, males of course, many of whom resented the trouble to which she put them and the need to accommodate a woman’s demands. And she was demanding! The house had to be equipped in particular ways, the teaching day needed a particular structure, and the location for lessons was almost always the city hall, where other administrative business was usually conducted but had to be put aside so she had the necessary time and space. Her intelligence, her courage, her way of dealing with obstacles thrown in her path, her perseverance—all this made me a huge admirer.

ES: The Machine. How revolutionary was it? How was it used as a teaching tool? What have you found in the archives about it? In my novel I reimagined Madame Du Coudray’s presentation of the Machine at Versailles … so I am particularly interested in your take on it.

NRG: The “machine” was absolutely revolutionary. Models of the female body existed before, of course, often in miniature and made of wood, stone, or ivory. But hers was life-size, and meant to be practiced upon, so built of strong yet pliable material. The internal structure was sometimes actual pelvic bone, but often a wicker frame, and it was covered in straw or upholstery and then a thick, durable outer fabric. There were vessels inside the mannequin that could hold water to imitate amniotic fluid, and of course there was the model of the fetus which could be placed in various positions to replicate difficult births—transverse, breech—that the practicing midwife might encounter and need to handle safely. The model was appreciated and approved by the Paris Faculty of medicine and the College of surgery, and Madame du Coudray and her team produced hundreds of these which got distributed everywhere she taught. A pristine model was always left to be permanently displayed in each town’s Hôtel de Ville, so that when the practice ones got damaged or worn out there would always be an intact replica showing how it should look when repaired. I understand there is now a replica of the Rouen original displayed in the Musée de l’Homme in Paris.

ES: Is Madame Du Coudray well known in France?

NRG: She is better known now than she was before. Until I visited the Musée Flaubert in Rouen—it is a history of medicine museum named for the novelist’s father who was a doctor—I didn’t even know there was an extant model. It was certainly not advertised! I was wandering through that museum and suddenly came upon it. I was so completely surprised that when I saw it I actually began to weep. I had worked with so many letters written by Madame du Coudray, but somehow standing in front of this amazing object, that she actually conceived of and sewed together herself, was unbelievably moving.

ES: You are not only the author of The King’s Midwife, but—most recently—of Minerva’s French Sisters described as : A fascinating collective biography of six female scientists in eighteenth-century France, whose stories were largely written out of history. How did they capture your attention?

NRG: I am always looking for the women in the Enlightenment. The French Revolutionary goal of “fraternité,” of brotherhood, always bothered me because we know there were women playing important instrumental roles in all aspects of political and intellectual life. But they are not talked about, Who were they? Where were they? In fact they can be found, but it takes a lot of determined sleuthing around. The anatomist in my new book, Mlle Biheron, was mentored by some of the same people who supported Madame du Coudray, so that was how I came across her. Then I learned of her partner, the botanist Mlle Basseporte at the Jardin du Roi. Then I learned of the field naturalist, Jeanne Barret who, disguised as man, got on Bougainville’s around-the-world voyage and collected flora from far-away lands that were then sent back to the Jardin. Through her I learned of the astronomer Mme Lepaute. I was led to the mathematician Mlle Ferrand and the chemist Thrioux d’Arconville through other channels. These six are by no means the only women doing serious science in France in the 1700s, but they were the ones about whom I was able to learn enough to really flesh out detailed stories of their works and days.

Nina Rattner Gelbart is professor of history and the Anita Johnson Wand Professor of Women’s Studies at Occidental College.